Patho-physiological mechanisms and consequences of gut edema

WSACS session at #EA18

Date | January 23, 2019 |

Modified | April 16, 2021 |

Author | WSACS |

In this Euroanesthesia #EA18 lecture Annika Reintam (Tartu, Estonia) discusses the Pathophysiological mechanisms and consequences of gut edema

Pathophysiological mechanisms and consequences of gut edema

Annika Reintam Blaser, MD, PhD (annika.reintam.blaser@ut.ee)

Tartu, Estonia and Lucerne Switzerland

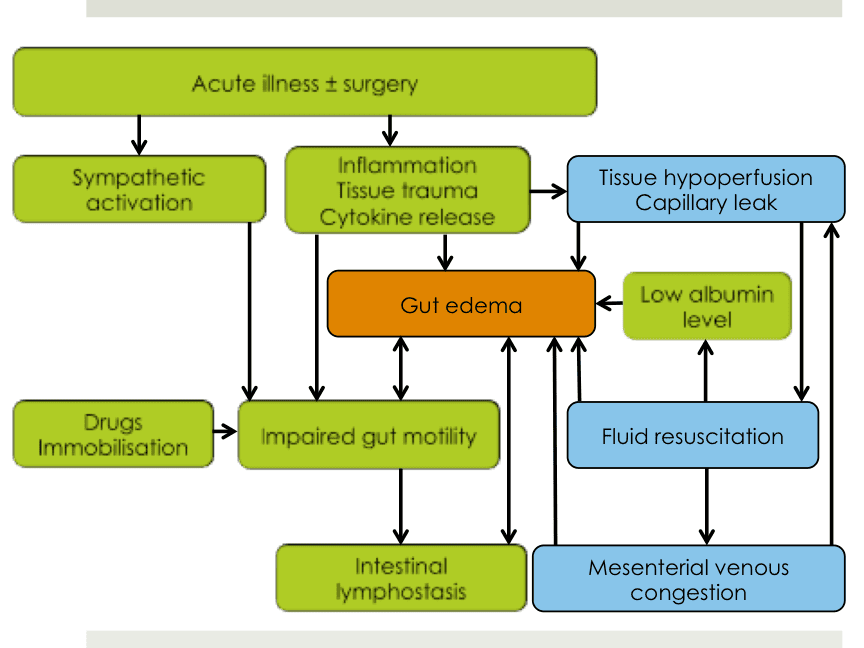

Gut edema in acute illness is not yet sufficiently studied and existing knowledge is largely based on experimental animal studies or small studies in healthy volunteers. However, increasing evidence confirms that gut edema impairs intestinal motility and healing of bowel anastomoses, being therefore an important contributor to outcome.

Current presentation focuses mainly on the role of fluids in development of intestinal edema.

The magnitude of the edema seems to depend on

- type, amount, timing and rate of resuscitation fluids

- mesenteric venous pressure

- oncotic pressure in both intravascular and interstitial space

- possibly of concomitant arterial pressure

Edema activates similar pathways as mechanical stretch of the bowel. An experimental study in rats showed that activation of signaling pathways to intestinal edema is very similar to 2-hour application of mechanical longitudinal distension of the bowel to 122.5% from its original length. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2875413/

Such cell stretch with altered cytoskeleton explains bowel dysmotility and impaired healing of anastomoses related to gut edema, but is also a possible explanation for systemic effects leading to inflammation and multiple organ failure via damaged gut barrier integrity.

Importantly, effect of edema on bowel motility may be comparable to the effect of peritonitis or endotoxemia. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29251668

Crystalloids leave intravascular space and reach interstitial space fast. Colloids stay longer in circulation, but then also partially enter interstitial space. In general, fluids with longer elimination half-time also stay longer in the interstitial space. Intestinal interstitium normally has a low compliance, transferring fluids fast into lymphatics. Lymphatic flow is responsible for bringing interstitial albumin or other colloid molecules back into the circulation.

In patients with increased mesenteric venous pressure (caused by right heart failure, mesenteric hypervolemia for other reasons or increased intra-abdominal pressure), interstitial pressure raises and intestinal interstitial space may become a space with high compliance. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23747781

Lymphatic flow is then impaired due to compression via an increased pressure in interstitial space, and impaired gut motility (mesenteric lymph vessels are valve-less and lymphatic flow is therefore dependent on bowel movements). https://www.physiology.org/doi/10.1152/ajpgi.1988.254.3.G389

In summary, development, magnitude and persistence of gut edema is tightly related to fluid management. The body seems to interpret gut edema in a similar way as a mechanical stretch. Gut edema itself has dramatic effects on bowel motility, which may even be comparable to ongoing peritonitis.